A Quick Review

Christianity has a long-lasting problem: apparently, a just, merciful, and loving God will consign some persons to eternal suffering, or at the very least, eternal annihilation. There seems to be a deep psychological or even ideological aversion to universalism, which is the idea that all persons, sooner or later, will be saved and eternally united with God. So deeply entrenched is this aversion, that on the live chat feed of a YouTube featuring David Bentley Hart discussing universalism with several theologians, someone actually said (apparently in all seriousness) “universalism is depressing.”

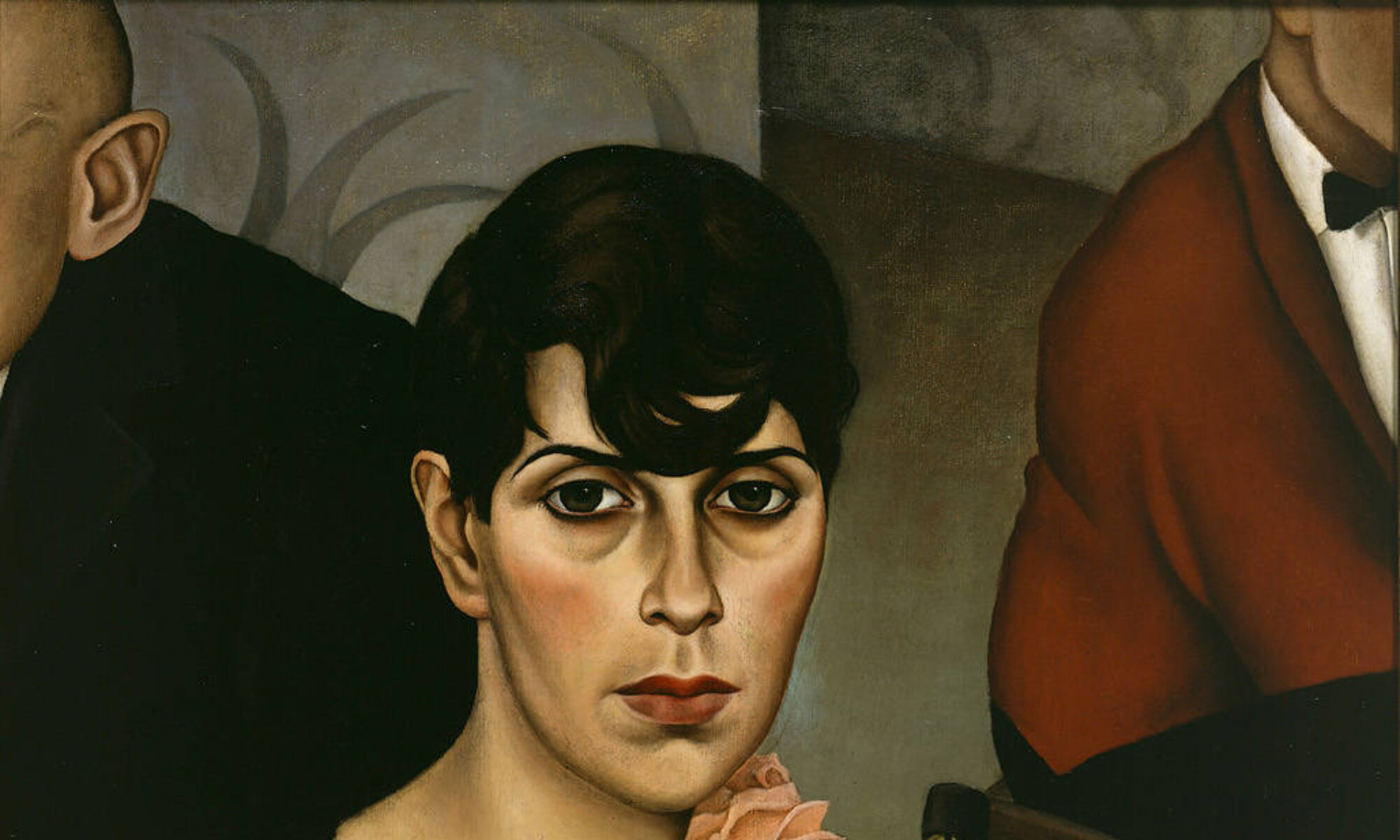

David Bentley Hart is a Christian of the Eastern Orthodox Church and a scholar of religion. His book is a defense of Universalism. I have read defenses of universal salvation before, but none so bold as David Bentley Hart’s. In fact, the last chapter, “Final Remarks,” begins thus:

Custom dictates and prudence advises that here, in closing, I wax gracefully disingenuous and declare that I am uncertain in my conclusions, that I offer them only hesitantly, that I entirely understand the views of those that take the opposite side of the argument, and that I fully respect contrary opinions on these matters. I find, however, whether on account of principle or of pride, that I am simply unable to do this. (199)

I laughed out loud for sheer delight when I read this, because it is time the infernalist position not only be rejected, but rejected without quarter. Indeed, Hart is even critical of Hans Urs von Balthasar, sometimes referred to as a “hopeful universalist,” because he wants to hold the infernalist and universalist positions apparently found in scripture “in a sustained ‘tension,’ without attempting any sort of final resolution or synthesis between them…. I [Hart] cannot quite suppress my suspicion that here the word ‘tension’ is being used merely as an anodyne euphemism for ‘contradiction’” (102-03). It is encouraging to hear a scholar of Hart’s repute take such a bold stand.

The book addresses and refutes on a rational basis the usual objections to universalism. One of these is that for human life to be meaningful humans must be free, and that genuine free will requires that individuals be free even to choose eternal hell, and that therefor damnation for some is at least possible. Part of Hart’s critique of this view involves assailing the conception of freedom implied here. Another objection to universalism is that God, being God, can do what he wants and is outside our paltry understanding of what we might call just, good, or loving, etc., and therefor can torture certain persons forever without in the least diminishing any of these qualities in himself. Hart deals with this objection handily too, as well as others, showing that we cannot defend infernalism by letting our conception of the divine retreat into some ineffable mystery as a cover for sheer cruelty.

One thing this book does not do is undertake a thoroughgoing scriptural analysis of what the Bible might be saying about hell, nor does it pretend to do this. Hart restricts the book mostly to a rational refutation of the idea of eternal hell. I don’t know what his stance is on Biblical inerrancy or infallibility, but he is not prepared to sacrifice reason to scripture, if scripture speaks nonsense.

I have been asked more than once I the last few years whether, if I were to become convinced that Christian adherence absolutely requires a belief in a hell of eternal torment, this would constitute in my mind proof that Christianity should be dismissed as a self- evidently morally obtuse and logically incoherent faith. And, as it happens, it would. (208)

But it is not Hart’s contention that scripture does speak nonsense on this score. He presents around the middle of the book numerous Bible passages which state or strongly suggest universalism.

To me it is surpassingly strange that, down the centuries, most Christians have come to believe that one class of claims—all of which are allegorical, pictorial, vague, and metaphorical in form—must be regarded as providing the “literal” content of the New Testament’s teaching regarding the world to come, while another class—all of which are invariably straightforward doctrinal statements—must be regarded as mere hyperbole. (94)

If one can be swayed simply by the brute force of arithmetic, it seems worth noting that, among the apparently most explicit statements on the last things, the universalist statements are by far the more numerous. (95)

Nor does Hart back off and give annihilationism (the belief that the damned are not tormented forever, but at some point annihilated) any quarter.

Hart is unintimidated by authority (Augustine or Aquinas, for example) or some idea of what we are “supposed” to believe according to such persons. He has a distinct attraction to certain of the early church fathers, such as Gregory of Nyssa. Calvin, however, comes in for some very hard knocks here. In a YouTube somewhere (I quote from memory) Hart has joked, “some people think I hate Calvin. And that’s because I do.”